In the fall of 2003, I took Dr. Monte Luker’s course in Old Testament Theology at Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary. The notebook full of my notes and work from the course is lined up with about twenty similar compilations on a shelf above my desk. I have found it useful once in a while to take down one of those notebooks and look through it for a brief refresher on some of the things I used to know.

In Dr. Luker’s course, we learned (temporarily in my case) some basic Hebrew and did some simple translations. One assigned task was to translate Psalm 29 to English and write a brief (single page) comment on it’s genre, literary form, structure, possible use, and meaning. We had learned, for example, that most Psalms can be classified as Laments, Hymns of Praise, or Songs of Thanksgiving, and it doesn’t take long to decide that Psalm 29 is a Hymn of Praise.

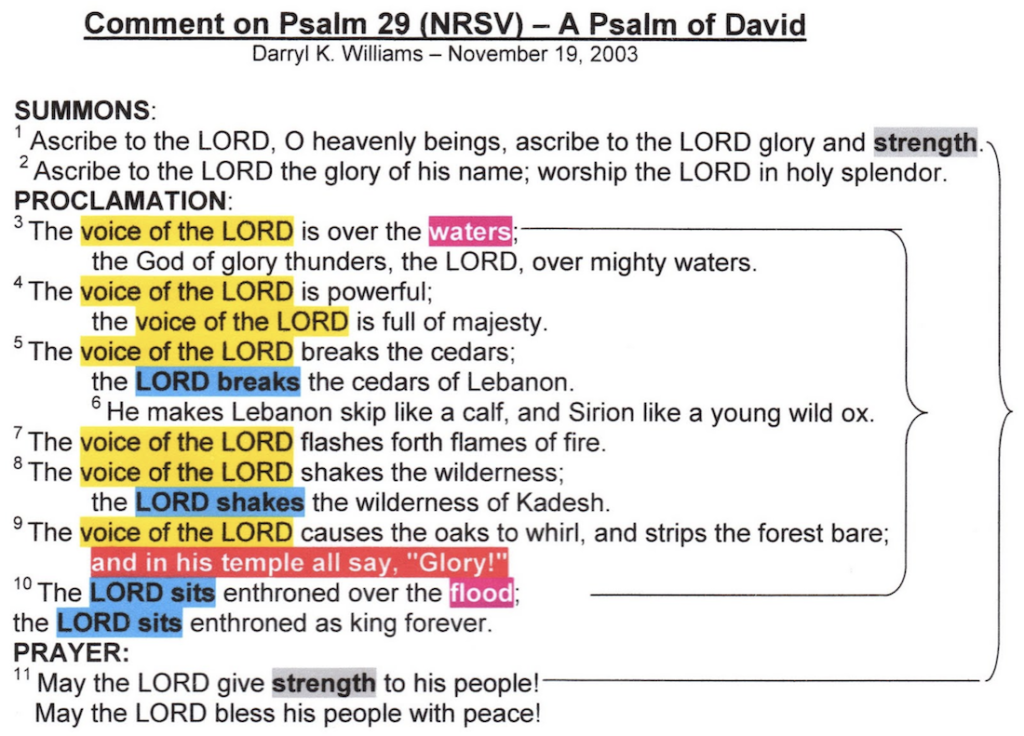

I learned to enjoy playing around with structure of Bible passages by formatting and highlighting of similar or common words and phrases because it helps ferret out the focal point. That kind of treatment of Psalm 29 can result in something like this:

And here is what I wrote about the Psalm in November, 2003:

The 29th Psalm is a hymn of praise consisting of a summons of imperatives (“give” or “ascribe” and “bow down” or “worship”) followed by a proclamation about the majesty and power of the voice of the LORD. The hymn is concluded in verse 11 with a prayer that the LORD will give strength to His people and bless them with peace. “Strength may be seen as an inclusio, ascribed to the LORD in verse 1 and then given by him to his people in verse 11. Just inside that inclusio are ‘waters” in verse 2 and “flood” in verse 10. The phrase “voice of the LORD” is used seven times, interrupted by proclamations of what the LORD does. This Psalm could have been used as a responsive reading in liturgical worship.

The proclamation uses the dramatic and destructive wonders of nature to show the power of God in this Psalm. Thunder is used frequently in scripture, particularly in Exodus and Revelation, as an indicator of the presence of God. The breaking of the cedars may imply strong wind, flames of fire may imply lightening or wilderness fires, and shaking of the wilderness may be due to earthquakes. Either wind or fire could strip the forest bare. Within the proclamation, there is strong identity of the LORD with the voice of the LORD. The proclamation easily shifts from one to the other as subjects of similar verbs as in verse 5 where the voice breaks the cedars and then the LORD breaks the cedars.

Broyles (Craig C. Broyles, New International Biblical Commentary: Psalms (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1999), 151-153.) points out that the Caananite worshipers of Baal would have been very familiar with the idea of associating these natural wonders with God and suggests that the Israelites may have modified an existing Canaanite hymn to Baal. But in the Psalm, there is no worship of nature or of the wonders of nature. God is in control and is over even the flood, forever. It is interesting that the summons is addressed to “heavenly beings” or sons of God and not to the people, and that also may be explained by having borrowed from the Canaanite religion. However, the heavenly beings are not gods, as the Canaanites might have thought, but are ones who bow down to and worship the LORD.

There is a striking contrast in the Prayer with the details of the proclamation. In spite of the mighty power and wonder of God, the prayer is that he bless his people with peace.